- -

- - - -

- - - -

- -

- -

- - - -

- - - -

- -

- - - - - -

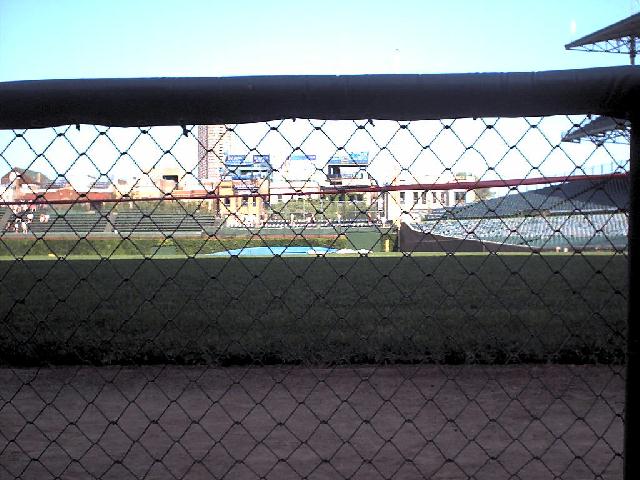

Game shots from 9/28/03 game against

the Pirates.

Shots of empty stadium and clubhouses

from August

'03 tour of the stadium.

2003 NB |

|

Wrigley

Field was built on the site of a seminary, and the corner of Clark and

Addison has been a sacred place ever since. One of the most famous places

of any kind in any city, the stadium is a reminder of how great baseball

used to be.

Since it was

founded with the motto urbs in horto, or "city in a garden," the

city of Chicago was a physical paradox, with the filth and noise of its

factories alongside the verdant serenity of its parks. Wrigley Field's

pastoral purity is part of what makes it timeless; the sight of the smooth

green lawn stretching toward the ivy tumbling down the outfield wall provides

a refreshing escape from the din and dirt of city life. There is no odious

JumboTron to ruin the view, as there is in every other major league park.

For a long time, in fact--until the emergence of slugger Sammy Sosa and

the Cubs' premier young pitching staff--the stadium itself was the main

reason to go to a Cubs game.

The odd thing

about Wrigley's prominence as a living monument to baseball is that it

has a far more illustrious history as a football stadium. Few fans

remember that Wrigley Field hosted the Chicago Bears from their move to

Chicago in the 1920's to their move to the lakefront in the early 70's.

In fact, no other football stadium has hosted more NFL games than Wrigley

Field (New Jersey's Meadowlands, which hosts both the Giants and the Jets,

will finally break that mark in a year or two). And the players that took

the gridiron here include the most storied in Bears history--Dick Butkus,

Gale Sayers, Mike Ditka, and coach (and Cubs fan) George Halas. But where

Yankee Stadium and Fenway Park are standing-room-only for the ghosts of

their Hall-of-Famers, as a baseball stadium, Wrigley just doesn't have

as many heroes and great moments (one would-be legend, Babe Ruth's called

shot, was a myth; he didn't really point to center field before hitting

a home run). In fact, when the Cubs lost to the Red Sox in the 1918 World

Series, they played at Comiskey Park, not Wrigley Field, which was too

small at the time. That's not to say there were some big baseball firsts

here; Wrigley was the first ballpark to let fans keep foul balls, the first

to have an organist, and the first to build a permanent concession stand.

There are other

reasons to tame one's romanticism about this picturesque ballpark, including

the yuppie fans who populate it. The glut of Eddie Bauer-clad, Big Ten

alum Lincoln Park loft-dwellers with a cell phone in one hand and a beer

in the other is not what baseball is all about (although, to their credit,

Cubs fans are into the game; they form one of only four or five big-league

crowds to roar for strike two against the visitors and ball three for the

home team). Spare us talk of how this Lexus-driving crowd is "long-suffering."

Since the early

1980s, there's been another ugly dent in the Cubs' cuddliness, and that's

the Tribune Company. The same behemoth that owns the Chicago Tribune and

WGN TV and radio, and recently gobbled up a chain of newspapers from Los

Angeles to Orlando to New York, is now the custodian of this baseball treasure.

Already the Tribune Company plunked lights on Wrigley's roof (which I'm

OK with; some night games can be nice, and few realize that Cubs' owners

had pondered putting lights up in the 40's) and plans to put seats over

the south sidewalk of Waveland. The day is coming--perhaps not for 20 or

50 years, but coming nonetheless--when the powers that be decide that the

stadium is just too creaky and cramped and build a place of comfort and

profit (hopefully it will not be greeted as eagerly by the Tribune newspaper

as when, during the lights controversy of 1988, an editorial called for

"a Wrigley Field replica in the suburbs" and "hole in the ground left at

Clark and Addison").

The most important

part of Wrigley's mystique is its physical participation in its neighborhood

and city. Most pro sports stadiums are self-contained and stranded in vast

parking lots (or, in a recent twist, built as retro replicas in reviving

industrial areas). Wrigley embraces its surrounding blocks--Clark, Addison,

Sheffield, Waveland, and beyond--and enlivens its unique North Side neighborhood

(Wrigleyville, as realtors and beer ads call the area). Wrigley has streets,

apartments, bars, El trains, and atmosphere around it. This is what

sports used to mean to cities, before fans' and teams' suburban migration,

and it's why the stadium is irreplaceable as a sports treasure.

Until that

suburban replica is erected, I relish the fact that, for all the nostalgia

that sustains baseball, for all of the wistful reflections I've heard from

fans of the old Brooklyn Dodgers or Yankee greats like Mickey Mantle, I'll

someday be able to tell my son or daughter how I used to take the Red Line

to watch Hall of Famer Sammy Sosa and the Cubs at Wrigley Field.

"Wow, Dad,"

they'll say. "Was that before they were renamed the Chicago Tribs?" -NB

The ballpark

we love is many things. It is a museum and a hot dog joint. It is a day

at the beach and a night in the rain. It is a national monument and a neighborhood

hangout. It is a circus and a cathedral. It is a delightful contradiction.

On the one hand, it is a time capsule, infused with history. On the other

hand, it maintains an everyday familiarity and a willingness to change

at a moment's notice. Wrigley Field is both a celebrity and a good friend.

It is priceless jewelry that you can wear. ... [It] has refused to age gracefully.

It has refused to age, period.

-Mark Jacob,

Wrigley Field: A Celebration of the Friendly Confines

-History

of Wrigley Field from Cubs.com

-Review

of Wrigley Field from ESPN.com's Jim Caple

-Review

of Wrigley Field from ChicagoBarProject.com

Coming soon:

Timeline of Wrigley history |