|

- - - -

- -

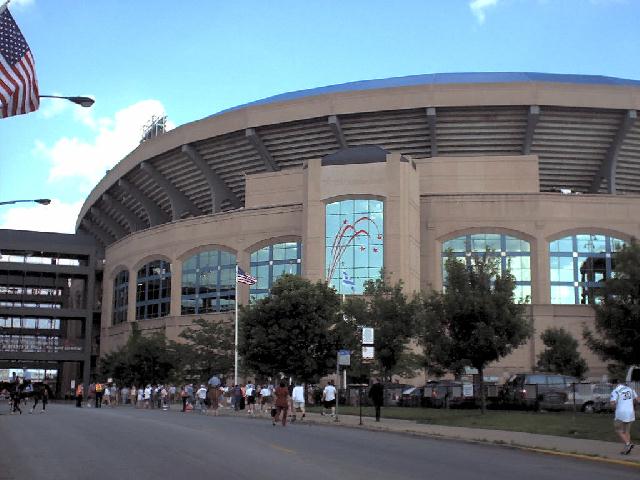

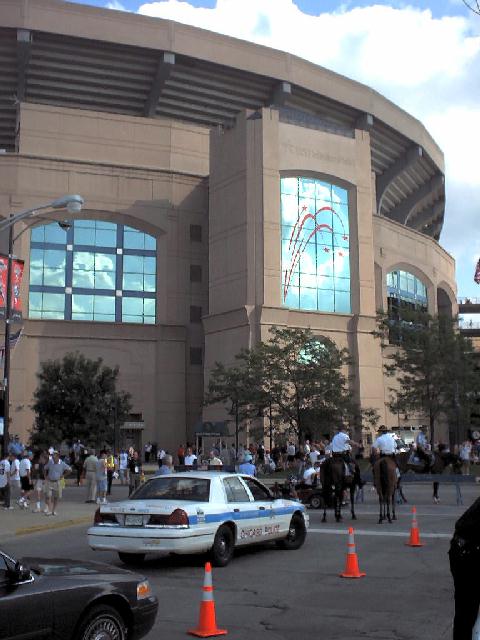

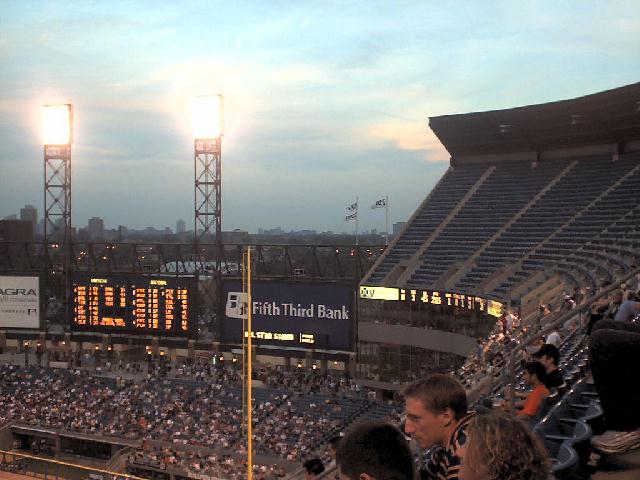

Exterior shots taken on the day of the 2003 All-Star Game. Interior shots taken during game v. Devil Rays, in which Frank Thomas hit his 400th home run.

2003 NB |

|

New

Comiskey | Old Comiskey | Comiskey Park

Timeline

When

it was finished in 1991, the new Comiskey Park peered over the roof

of the old one, scornfully, it seemed--a manifestation of the contempt

White Sox management had for their current stadium. The new facility was

everything the old one wasn't--spacious, clean, and laced with plenty of

luxury boxes. But the dissimilarities didn't end there. While the old park

had charm and history, the new one looked artificial and disposable. The

old park let you feel close enough to the players to hear them cuss; the

new park--whose front row seat in the upper deck was farther from the field

than the last row of the old park--was a vast chasm ("like looking into

a pit," one fan told the Chicago Tribune). Most importantly, the

old park was an integral part of Armour Square, its neighborhood on the

South Side. The new stadium, which now sits in an urban desert of parking

lots, plainly wants nothing to do with those who can see it from their

front porches. If it did, White Sox management would have gone about planning

the new Comiskey much differently. Instead, the new stadium's history is

a sorry tale.

Many people

forget that back in 1984, before the franchise's infamous flirtation with

St. Petersburg, the White Sox had purchased a 140-acre site in Addison

(the suburb, that is, not the street the Cubs play on), and applied for

a government bond to build a new stadium there. The Sox wanted out of the

South Side. Once, White Sox players had been kindred spirits with their

working class neighborhood fans; by the mid-1980s, the team "felt ... exiled

in an unfriendly setting," write Larry Bennett and Costas Spirou in It's

Hardly Sportin': Stadiums, Neighborhoods, and the New Chicago. "It

would be part of white flight, but that isn't the reason for the move,"

owner Jerry Reinsdorf told the Chicago Tribune at the time. "The

fans moved away from the South Side. Why can't we?"

But Addison

didn't want big-league ball in its backyard, and in December of 1986 the

White Sox made a deal with the state of Illinois for a $120 million new

stadium on 35th Street, across from the old Comiskey, funded by taxpayers.

All seemed well. But in 1987, as the state and the city fought for control

of the paperwork on the project, the team started glancing seductively

at the city of St. Petersburg, Florida, which was building its Suncoast

Dome and needed a reason to fill it. By early 1988, local government's

wrangling over the Chicago project worsened, delaying the opening of the

stadium from Opening Day 1990 to 1991, and the White Sox were swooning

over St. Pete, which was offering succulent rental rates for the Suncoast.

The franchise went back to the city of Chicago and demanded a better deal

or they would pack their bags.

I was eight

at the time, and I remember seeing television highlights of players hitting

fly balls in the Suncoast Dome to see if the ceiling was high enough for

big league ball. Back in Chicago, the idea of losing a civic institution

to a small Sun Belt city was revolting. The media blasted the government

for failing to sign a new stadium deal for the White Sox and endangering

their future in town, momentarily forgetting that the White Sox already

had a deal to stay in Chicago. Finally, in a midnight session in June

of 1988, the Illinois legislature agreed to a new stadium deal. Taxpayers

would now pay $150 million for the new park, not $120 million, and the

government would agree to cancel the team's rent and pay for a few hundred

thousand tickets if attendance fell to 1 million people per year. The White

Sox would stay put after all. Former Sox executives have since said the

team was never serious about moving. They just wanted to shake down the

state for more money.

Because of

the political climate of the new stadium's origins--the city's political

tussles, the team's threat to migrate South, and the fact that the Cubs

were generating another controversy on the North Side with their plans

to put lights on Wrigley Field--a lot of things that should have happened

didn't. Armour Square residents weren't given a serious chance to voice

their opinions about the where the new stadium should go and how they would

be compensated for relocating. An intriguing idea from the organization

Save Our Sox, which called for the restoration of the old Comiskey as a

national monument and historic tourist site, failed to win support as the

panicking city and fans looked for a simpler solution. The same was true

of Armour Field, a plan by New Urbanist architect Philip Bess for a more

thoughtfully designed "urban ballpark," which would lie just north of the

old one and would actually interact with its surroundings, as does Wrigley

Field.

As Bennett

and Spirou put it in their book:

Both the ...

proposals aimed to tie stadium development to the adjoining neighborhoods'

long-standing identity. In each case, advocates sought to present major-league

baseball in a physical setting that matched their particular sense of tradition.

Each of these alternative proposals viewed a professional sporting facility

as an institution whose character could be enhanced by and, in turn, could

enhance its local neighborhood enivironment. Such thinking clearly did

not loom large in the minds of White Sox and [government] executives.

Instead, the

Sox wanted and got a truly "suburban" structure, a plastic-looking, self-contained,

parking-lot-skirted, vacuous stadium with little originality and not a

drop of timelessness.

The

greatest travesty of the new Comiskey is how it deliberately fails to embrace

its neighbors despite being built with their tax dollars. The whole point

of having the government pay for the new stadium--at least originally,

before the government was held at gunpoint and just wanted to keep the

team in town--was that the stadium would enrich what had become an impoverished

area by creating jobs and street life. Bars, other businesses, and apartments

could have been built around the park (as Bess' design specifically called

for), turning the area into an actual place, not just a location. Local

residents could have lived and made a living in the park's shadow. It could

have been the South Side's answer to the Wrigley Field's Waveland and Sheffield

streets. But what did the White Sox do? They put a clause in their stadium

deal that no businesses could operate in proxmity to the park. A restraining

order. A clause that prevented the exact economic boost they promised.

As a result,

"Comiskey Park has clearly not set off streams of auxiliary economic development,"

write Bennett and Spirou. In fact, the authors found that the area actually

lost jobs in the six years after the stadium opened. "It is also evident

that the new ballpark has not contributed to upgrading its immediate environment."

In one final

symbolic insult, which Bennett and Spirou document with palpable disgust,

the franchise refused to build around or relocate McCuddy's Tavern--which

stood across from the old park, and to which, as the story went, Babe Ruth

used to sprint between innings for a quick brew (the pub proudly displayed

a piece of carpet he was said to have torn with his cleats). It took an

hour to tear McCuddy's down."The fate of McCuddy's," the authors write,

encapsulates the broader failure to link stadium development and effective

community development in the new Comiskey Park project."

The message

was clear. This will be a stadium you drive to, park around, get in, get

relieved of your money, and get back out again. This will not be a vital

environment. This will be a disconnected destination. That's why it's so

aggravating to read at

WhiteSox.com that the franchise is "part of a uniquely historic Chicago

neighborhood filled with excellent eating and drinking establishments.

In and around [sponsored stadium name], fans are treated to great food

and good times at some of the finest restaurants and bars in the city."

Their consistent approach to, or reproach of, the community has made any

talk from the White Sox franchise of "community relations" pure crap, brown

and sticky. They had their chance, and the result is this forbidding monstrosity.

In an interiew

with Bennett and Spirou in the Chicago Tribune, I asked them if it was

too late for the team to make a meaningful connection with its neighbors.

It was not, they said (the team could start by letting some businesses

open on the same block). But, said Bennett, "Ultimately I don't think Jerry

Reinsdorf wants that."

And, some might

wonder, why should he? As principal architect Rick deFlon, who gets defensive

about complaints of the park's desultory design (and whose firm ironically

went on to design beautiful neighborhood-friendly ballparks in Baltimore

and Cleveland), said; "I'm a dinky little stadium architect. I'm not trying

to design cities." But the Chicago Tribune's Blair Kamin aptly responds:

"It isn't asking too much for a taxpayer-financed public works project

to being healing the city's wounds."

In 2003, one

final link to history was severed; the franchise sold the naming rights

for Comiskey Park to a cell phone company. But they're not paying me anything

to say the new name, so I won't.

UPDATE: After the 2003 season, the White Sox embarked on a $28 million renovation of their ballpark with the intention of making the upper deck more fan-friendly.

Wrote Blair Kamin: "Now, 12 years later, it is remarkable to see a publicly funded stadium that cost nearly $135 million being ripped apart to make it resemble the ballpark it should have been in the first place."

|

- -

- - - -

2003 NB

|

|

Old Comiskey

Park

Of

Chicago's two most famous ballparks, the old Comiskey and Wrigley Field--which

were both designed by Zachary Taylor Davis--you could argue that Comiskey

was a fitter icon of the city's history. Only Comiskey exhibited Chicago's

working class heritage, planted as it was in a workaday neighborhood. Before

the age of millionaire athletes, the gritty players provided fans with

relevant heroes (and the team's miserly owner, Charles Comiskey, nonetheless

provided them with cheap bleacher seats). Only in Comiskey could you smell

the stockyards. Only in Comiskey could you regularly see the first Mayor

Daley in his box seat.

Towards the

end of its life Comiskey surrendered its dignity to the gimmicks of eccentric

owner Bill Veeck. Among the earliest was the scoreboard that, back in 1959,

was rigged to launch fireworks after White Sox home runs (a tradition that

continues in the new park). The most infamous was Disco Demolition Night

in the summer of 1979. Fans could get in for under a buck if they brought

a disco record to contribute to a bonfire. But when the fire was lit the

crowd rushed the field and made such a mess that the White Sox had to forfeit

the second game of a doubleheader.

One oddity

of baseball lore is that although the White Sox have one of the longest

championship droughts in sports, you hardly ever hear about it. The Cubs'

famous futility--and their curse of the Billy Goat--and the Boston Red Sox' woes--and

their curse of the Bambino--are much more legendary, even though the White

Sox haven't won the World Series since 1917 (the Cubs last won in 1908

and the Red Sox in 1918). Perhaps this is because the White Sox had their chance in 1919, when they were favored but threw the World Series. No Sox team has won since. Call it the curse of the Black Sox.

Today, all

that is left of the old Comiskey is the batter's box and home plate etched

in the middle of a parking lot across from the new park. Painted foul lines

stretch the length of the former field. The Chicago Tribune wrote

that putting a parking lot on the site of the old Chicago Stadium ensured

"a future of oil leaks where legends once cavorted." The same is true of

the old Comiskey. Today, idle sedans and SUV's from the suburbs drip on

this hallowed ground where 80 years of baseball history (see below)

happened.

Blair Kamin:

The old park

wasn't pretty, but when you plopped down in one of its green wooden seats,

you felt close enough to the field that you could reach out and touch home

plate, smell the turf, and hear what was going on when the catcher, pitcher,

and manager conferred on the mound. And you knew you couldn't be anywhere

else. ... The real test of a ballpark is how well it lets fans taste the

flavor of baseball. It's a game of nuances--the pop of a fastball in the

catcher's mitt versus the soft thud of an off-speed pitch--so it thrives

on intimacy.

-from Why

Architecture Matters |

|

|

Comiskey

Park Timeline

July 1,

1910

White Sox

Park opens; owner Charles Comiskey pronounces it "baseball palace of the

world."

October

13, 1917

White Sox

beat the New York Giants 8-5

to go up three games to two in the World Series. Two days later they win

in New York to clinch the championship, their second ever and last to this

day.

September

5, 1918

Playing at

Comiskey, the Chicago Cubs lose to Boston in Game

1 of the World Series.

October

9, 1919

White Sox

lose Game 8 of the World Series 10-5

to the visiting Cincinnati Reds to drop the series five games to three.

Two years later, jury acquits eight "Black Sox" players of throwing the

series, but Commissioner Landis bans them from baseball for life.

July 6,

1933

First Major

League All Star Game created by the Chicago Tribune to coincide with Chicago's

World's Fair. Babe Ruth hits two-run homer to lift the American League

to a 4-2 win.

Sept. 10,

1933

First

Negro League All-Star Game.

June 22,

1937

Joe

Louis defeats James Braddock for his first heavyweight title.

July 5,

1947

Larry Doby,

pinch hitting for the visiting Cleveland Indians, becomes the first African

American to play in the American League.

Dec. 28,

1947

Wearing tennis

shoes for traction on the slippery field, the Chicago (now Arizona)

Cardinals defeat the Philadelphia Eagles 28-21 for their

only NFL championship.

July 11,

1950

In the first

extra-inning All-Star Game, Ted Williams' fifth inning RBI single gives

the American League the lead (the National League went on to win 4-3 in

14 innings). After the game Williams learned that he broke his left elbow

in the first inning while crashing into the outfield wall for a catch.

May 1,

1951

Minnie Minoso

becomes the first African American to play for the White Sox. In his first

at bat, he hits a home run.

September

25, 1962

Sonny

Liston knocks out Floyd Patterson to win his first heavyweight title.

August

20, 1965

The

Beatles perform two concerts, their only outdoor appearances in Chicago

July 12,

1979

Disco Demolition

night turns riotous, leading to a White Sox forfeit of the second game

of a doubleheader

Sep 22,

1981

Chicago

Sting defeat the San Diego Sockers to advance to the finals of of the

North American Soccer League.

July 6,

1983

Angels' Fred

Lynn hits first-ever All Star Game Grand Slam to lead the American League

to a 13-3 victory.

New Comiskey:

April 9,

1993

Bo Jackson

becomes the first player in history to play with an artificial hip. He

knocks his first pitch out of the park.

July 15,

1994

During a game,

Cleveland Indians pitcher Jason Grimsley breaks into umpires' dressing

room and removes

teammate Albert Belle's confiscated corked bat. He replaces the bat

with one that--alas--bears the name of teammate Paul Sorrento.

August

12, 1994

With the White

Sox in first place, major league players go on a season-ending strike.

Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf is perceived to be instrumental in prompting

the players' strike.

June 16,

1997

White Sox

host Cubs in first-ever regular season meeting, lose 8-3 before taking

the next two games.

Sept. 28,

1997

Frank Thomas

finishes season with .347 average, becoming the second Sox player ever

to win the American League batting title.

July 15,

2003

American League

wins All-Star Game 7-6;

first time the game decides home field advantage in the World Series.

See also:

-It's

Hardly Sportin': Stadiums, Neighborhoods, and the New Chicago by

Larry Bennett and Costas Spirou

-My interview

with the authors: "Are Chicago's professional sports stadiums good neighbors?"

Chicago

Tribune, April 17, 2003

-"Take me

out to (and in) the ballparks," Lou Carlozo, Chicago Tribune, July

18, 2003

-"[Comiskey]

all aglow, but poverty in shadows," John McCormick, Chicago Tribune,

July 13, 2003

-More

about New Comiskey from Ballparks.com

-Picture

of New Comiskey from Ballparks.com

-More

about New Comiskey from WhiteSox.com

-More

about New Comiskey from BallparksofBaseball.com

-More

about Old Comiskey from Ballparks.com

-More

about Old Comiskey from WhiteSoxInteractive.com

-Pictures

of Old Comiskey from WhiteSoxInteractive.com

-Pictures

of Old Comiskey from StadiumPage.com

-1991

picture of the two adjacent Comiskey Parks from Ballparks.com

-History

of both Comiskey Parks from WhiteSox.com

-Team

timeline from WhiteSox.com

-More

about the Black Sox from the Chicago HIstorical Society

-More

about the Black Sox trial from Famous Trials Online

-Chicago

White Sox all-time stats from Baseball-Reference.com |

|

|